Chapter 3: A First Bayesian Analysis of Unknown Probabilities

Chapter03.RmdSection 3.1: Data arising from a homogeneous population: The beta-binomial model

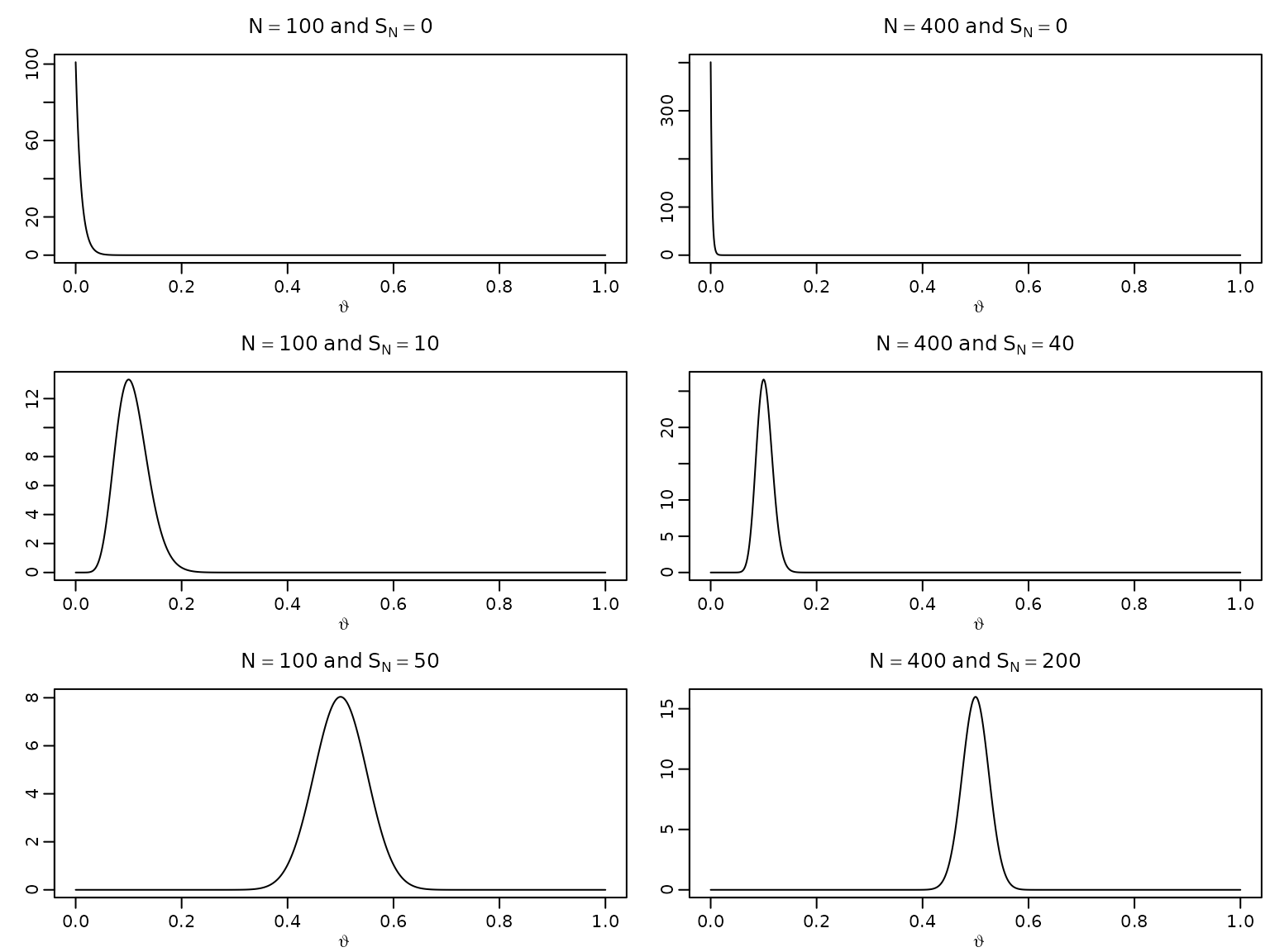

Figure 3.1: Posteriors under the beta-binomial model

To reproduce the posteriors in this figure, we simply need to plug in the respective counts into the expression for the posterior density and visualize it accordingly.

trueprop <- c(0, .1, .5)

N <- c(100, 400)

theta <- seq(0, 1, .001)

for (p in trueprop) {

for (n in N) {

aN <- n * p + 1

bN <- n - n * p + 1

plot(theta, dbeta(theta, aN, bN), type = "l", xlab = expression(vartheta),

ylab = "", main = bquote(N == .(n) ~ "and" ~ S[N] == .(n * p)))

}

}

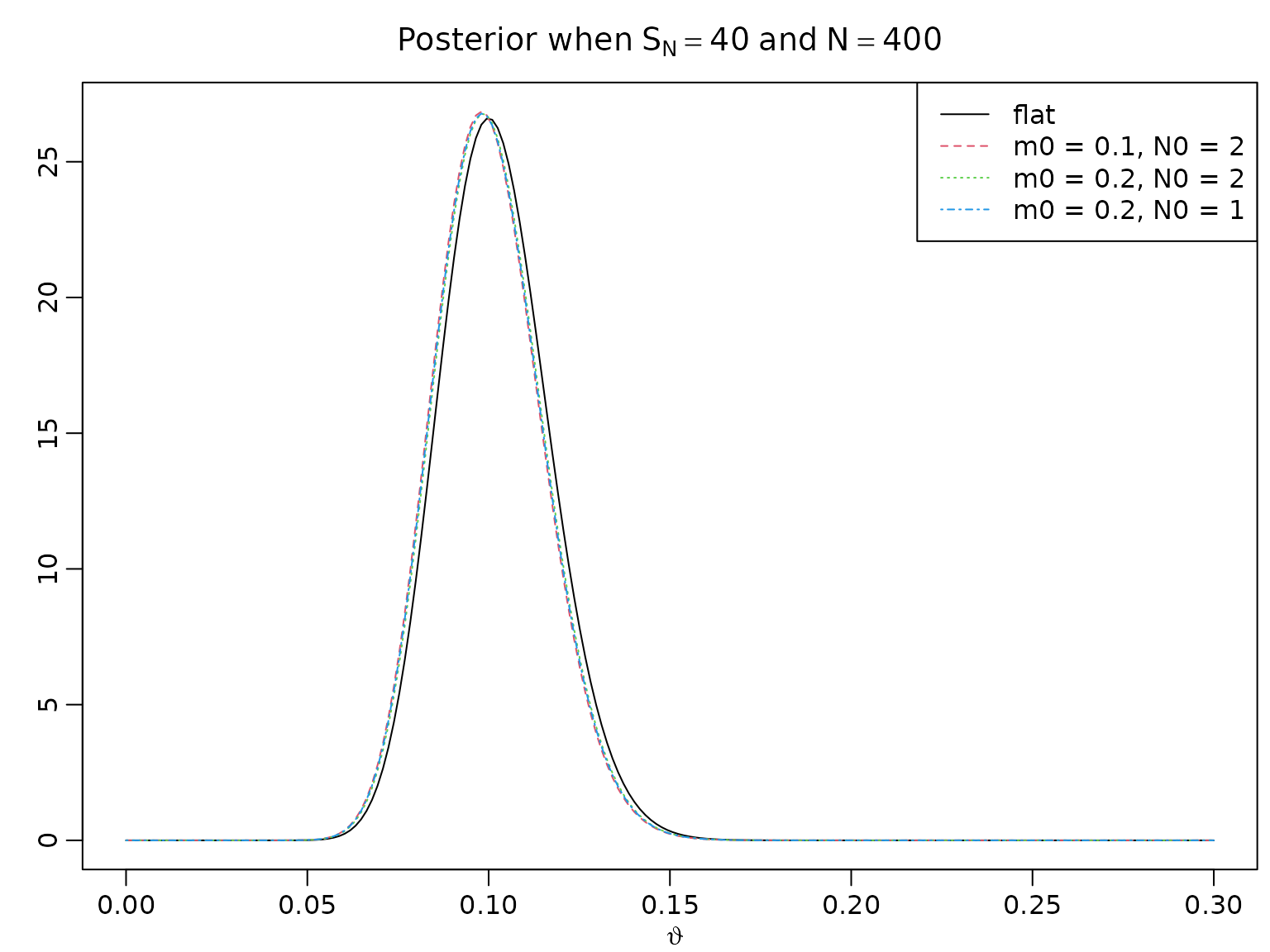

Calibrating the Beta prior

Let denote the prior mean and the strength of the prior information.

m0 <- c(.5, .1, .2, .2)

N0 <- c(2, 2, 2, 1)

a <- N0 * m0

b <- N0 * (1 - m0)

N <- 400

SN <- c(40, 4)

for (i in seq_along(SN)) {

aN <- SN[i] + a

bN <- N - SN[i] + b

theta <- seq(0, 3 * SN[i] / N, length.out = 200)

plot(theta, dbeta(theta, aN[1], bN[1]), type = "l", ylab = "",

xlab = expression(vartheta), ylim = range(dbeta(theta, aN, bN)),

main = bquote("Posterior when" ~ S[N] == .(SN[i]) ~ "and" ~ N == .(N)))

for (j in 2:4) {

lines(theta, dbeta(theta, aN[j], bN[j]), col = j, lty = j)

}

legend("topright", c("flat", paste(paste0("m0 = ", m0[2:4]),

paste0(" N0 = ", N0[2:4]), sep = ",")),

lty = 1:4, col = 1:4)

}

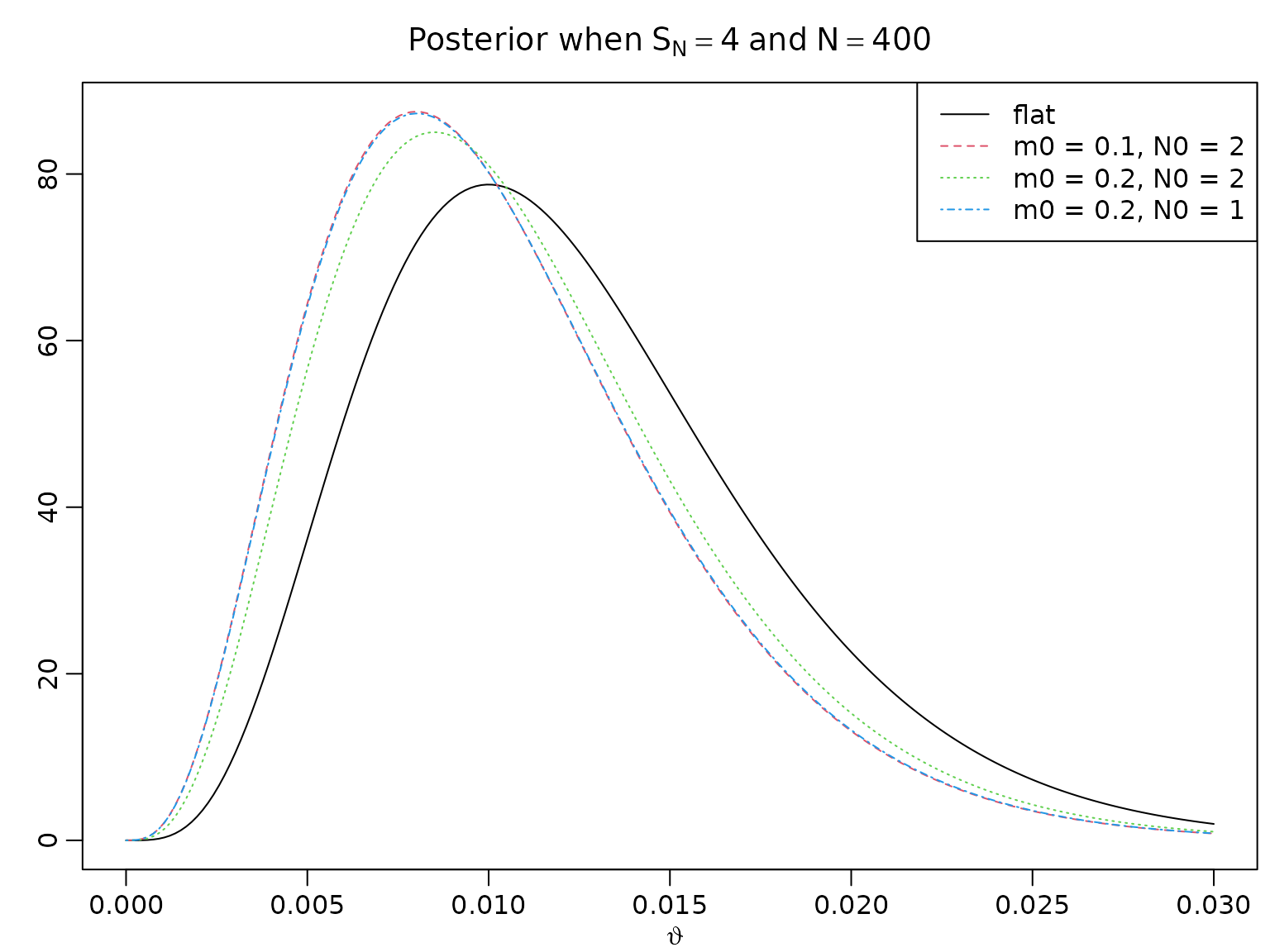

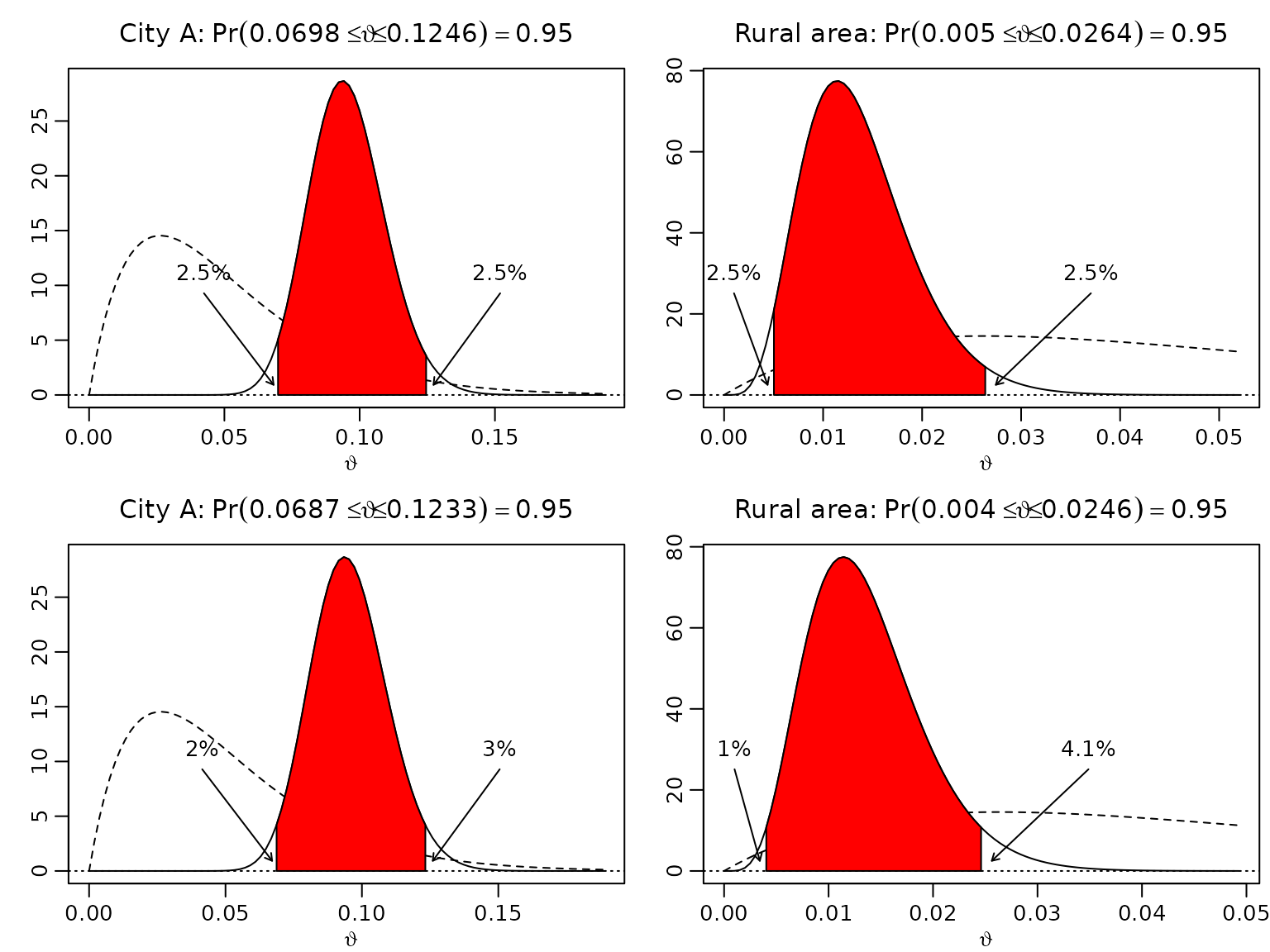

Example 3.1 / Figure 3.2: Uncertainty quantification for market shares

In city A, 40 out of 400 questioned people would purchase a certain product, in a rural community, only 4 out of 400. Assuming a uniform prior, we now compute equal-tailed intervals and highest posterior density (HPD) intervals. Note that R is (generally) vectorized, so we can compute the equal-tailed intervals without using a loop.

m0 <- 0.05

N0 <- 40

a <- N0 * m0

b <- N0 * (1 - m0)

N <- 400

SN <- c("City A" = 40, "Rural area" = 4)

aN <- SN + a

bN <- N - SN + b

gamma <- .95

alpha <- 1 - gamma

# Equal-tailed credible intervals

leftET <- qbeta(alpha/2, aN, bN)

rightET <- qbeta(1 - alpha/2, aN, bN)

# HPD intervals

resolution <- 10000

grid <- seq(0, 1, length.out = resolution + 1)

dist <- gamma * resolution

leftHPD <- rightHPD <- rep(NA_real_, length(aN))

for (i in seq_along(aN)) {

qs <- qbeta(grid, aN[i], bN[i])

minimizer <- which.min(diff(qs, lag = dist))

leftHPD[i] <- qs[minimizer]

rightHPD[i] <- qs[minimizer + dist]

}Now we visualize our findings.

left <- cbind(leftET, leftHPD)

right <- cbind(rightET, rightHPD)

for (i in seq_along(aN)) {

for (j in seq_len(ncol(left))) {

len <- right[i,j] - left[i,j]

theta <- seq(0, right[i,j] + 1.2 * len, length.out = 100)

plot(theta, dbeta(theta, aN[i], bN[i]), type = "l",

xlab = expression(vartheta), ylab = "",

main = bquote(.(names(aN[i])) * ":" ~ Pr(.(round(left[i,j], 4)) <=

{vartheta <= .(round(right[i,j], 4))}) == .(gamma)))

lines(theta, dbeta(theta, a, b), lty = 2)

abline(h = 0, lty = 3)

polygon(c(left[i,j], left[i,j],

theta[theta > left[i,j] & theta < right[i,j]],

right[i,j], right[i,j]),

c(0, dbeta(left[i,j], aN[i], bN[i]),

dbeta(theta[theta >= left[i,j] & theta <= right[i,j]], aN[i], bN[i]),

dbeta(right[i,j], aN[i], bN[i]), 0),

col = "red")

arrows(x0 <- max(left[i,j] - .5 * len, 0.001),

y0 <- .3 * diff(par("usr")[3:4]),

x1 <- left[i,j] - .03 * len,

y1 <- .03 * diff(par("usr")[3:4]),

length = .05)

text(x0, y0, paste0(round(100 * pbeta(left[i,j], aN[i], bN[i]), 1), "%"),

pos = 3)

arrows(x0 <- right[i,j] + .5 * len,

y0 <- .3 * diff(par("usr")[3:4]),

x1 <- right[i,j] + .05 * len,

y1 <- .03 * diff(par("usr")[3:4]),

length = .05)

text(x0, y0, paste0(round(100 * (1 - pbeta(right[i,j], aN[i], bN[i])), 1), "%"),

pos = 3)

}

}

Example 3.2 / Table 3.1: Posterior credible intervals under the beta-binomial model

We now proceed to computing credible intervals for the synthetic example.

Ns <- rep(N, each = length(trueprop))

SNs <- Ns * rep(trueprop, length(N))

aN <- SNs + 1

bN <- Ns - SNs + 1

# Equal-tails credible intervals

leftET <- qbeta(alpha/2, aN, bN)

rightET <- qbeta(1 - alpha/2, aN, bN)

# HPD intervals

resolution <- 10000

grid <- seq(0, 1, length.out = resolution + 1)

dist <- gamma * resolution

leftHPD <- rightHPD <- rep(NA_real_, length(aN))

for (i in seq_along(aN)) {

qs <- qbeta(grid, aN[i], bN[i])

minimizer <- which.min(diff(qs, lag = dist))

leftHPD[i] <- qs[minimizer]

rightHPD[i] <- qs[minimizer + dist]

}

res <- cbind(leftET, rightET, leftHPD, rightHPD)All the desired intervals are now stored and can be displayed.

| leftET | rightET | leftHPD | rightHPD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0001 | 0.0092 | 0.0000 | 0.0074 |

| 0.0744 | 0.1334 | 0.0732 | 0.1319 |

| 0.4512 | 0.5488 | 0.4512 | 0.5488 |

We can also compare their lengths.

res <- cbind(lengthET = rightET - leftET, lengthHPD = rightHPD - leftHPD)

knitr::kable(round(res, 4))| lengthET | lengthHPD |

|---|---|

| 0.0091 | 0.0074 |

| 0.0590 | 0.0587 |

| 0.0976 | 0.0976 |

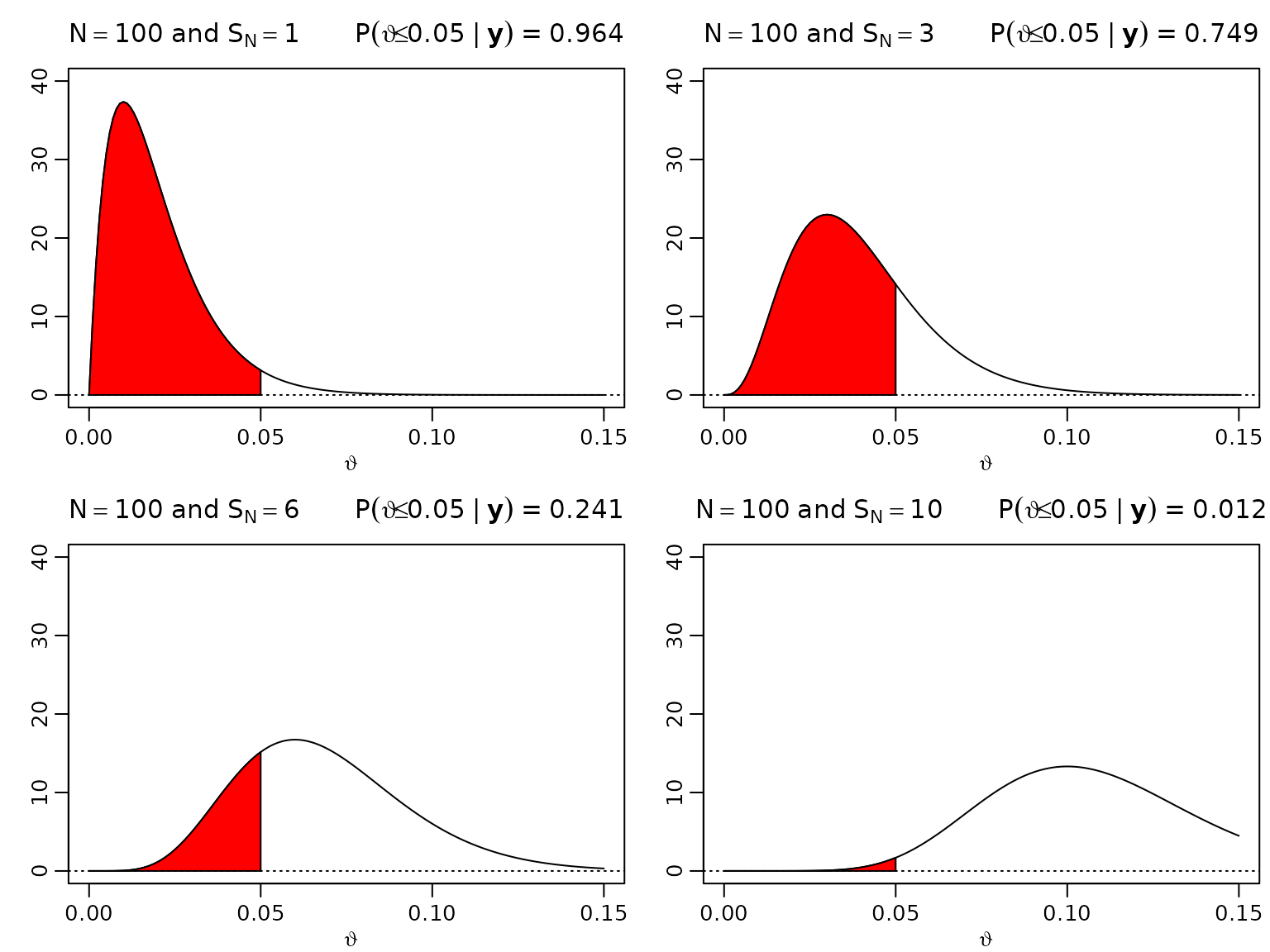

Figure 3.3: One-sided hypothesis testing

We now move forward to assessing visualizing the posterior probability of (the proportion of defective items) being less than for and .

theta <- seq(0, .15, .001)

N <- 100

SN <- c(1, 3, 6, 10)

aN <- SN + 1

bN <- N - SN + 1

for (i in seq_along(SN)) {

plot(theta, dbeta(theta, aN[i], bN[i]), type = "l", ylim = c(0, 40),

xlab = expression(vartheta), ylab = "",

main = bquote(N == 100 ~ "and" ~ S[N] == .(SN[i]) ~ " " ~

P(vartheta <= 0.05 ~ "|" ~ bold(y)) ~ "=" ~

.(round(pbeta(0.05, aN[i], bN[i]), 3))))

abline(h = 0, lty = 3)

polygon(c(theta[theta <= 0.05], 0.05),

c(dbeta(theta[theta <= 0.05], aN[i], bN[i]), 0), col = "red")

}

Example 3.4: Labor market data

We load the dataset from the package and extract the data needed for the anlaysis:

data("labor", package = "BayesianLearningCode")

labor <- subset(labor,

income_1997 != "zero" & female,

c(income_1998, wcollar_1986))

labor <- with(labor,

data.frame(unemployed = income_1998 == "zero",

wcollar = wcollar_1986))Cross-tabuling being unemployed (i.e., having no income) and being a white collar work gives:

table(labor)

#> wcollar

#> unemployed FALSE TRUE

#> FALSE 368 634

#> TRUE 62 59We estimate the risk for a woman who had a positive income, to have no income in the next year and assume that this risk is different for white- and blue-collar workers.

The four relevant data summaries are given by:

(N1 <- with(labor, sum(wcollar)))

#> [1] 693

(S_N1 <- with(labor, sum(wcollar & unemployed)))

#> [1] 59

(N2 <- with(labor, sum(!wcollar)))

#> [1] 430

(S_N2 <- with(labor, sum(!wcollar & unemployed)))

#> [1] 62Under a uniform prior, the parameters of the posterior distribution are given by:

aN1 <- 1 + S_N1

bN1 <- 1 + N1 - S_N1

aN2 <- 1 + S_N2

bN2 <- 1 + N2 - S_N2The posterior expectations are given by

aN1 / (aN1 + bN1)

#> [1] 0.08633094

aN2 / (aN2 + bN2)

#> [1] 0.1458333We visualize the joint posterior of using a contour plot as well as a density estimate of the difference .

if (pdfplots) {

pdf("3-2_1.pdf", width = 8, height = 5)

par(mgp = c(1, .5, 0), mar = c(2.2, 1.5, 2, .2), lwd = 2)

}

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

post <- function(x1, x2, aN1, aN2, bN1, bN2) {

dbeta(x1, aN1, bN1) * dbeta(x2, aN2, bN2)

}

vartheta1 <- seq(0.04, 0.13, length.out = 100)

vartheta2 <- seq(0.08, 0.22, length.out = 100)

z <- outer(vartheta1, vartheta2, post, aN1 = aN1, aN2 = aN2, bN1 = bN1, bN2 = bN2)

nrz <- nrow(z)

ncz <- ncol(z)

# Generate the desired number of colors from this palette

nbcol <- 20

color <- topo.colors(nbcol)

# Compute the z-value at the facet centres

zfacet <- z[-1, -1] + z[-1, -ncz] + z[-nrz, -1] + z[-nrz, -ncz]

# Recode facet z-values into color indices

facetcol <- cut(zfacet, nbcol)

contour(vartheta1, vartheta2, z, col = color,

xlab = bquote(vartheta[1]), ylab = bquote(vartheta[2]),

main = expression(paste("Posterior of (", vartheta[1],

", ", vartheta[2], ")")))

abline(0,1)

postdraws <- data.frame(vartheta1 = rbeta(10^6, aN1, bN1),

vartheta2 = rbeta(10^6, aN2, bN2))

postdraws$diff <- with(postdraws, vartheta2 - vartheta1)

plot(density(postdraws$diff),

xlab = bquote(vartheta[1] - vartheta[2]),

main = expression(paste("Posterior density p(", vartheta[1],

" - ", vartheta[2], "| y)")))

if (pdfplots) {

pdf("3-2_1.pdf", width = 8, height = 5)

par(mgp = c(1, .5, 0), mar = c(2.2, 1.5, 2, .2), lwd = 2)

}

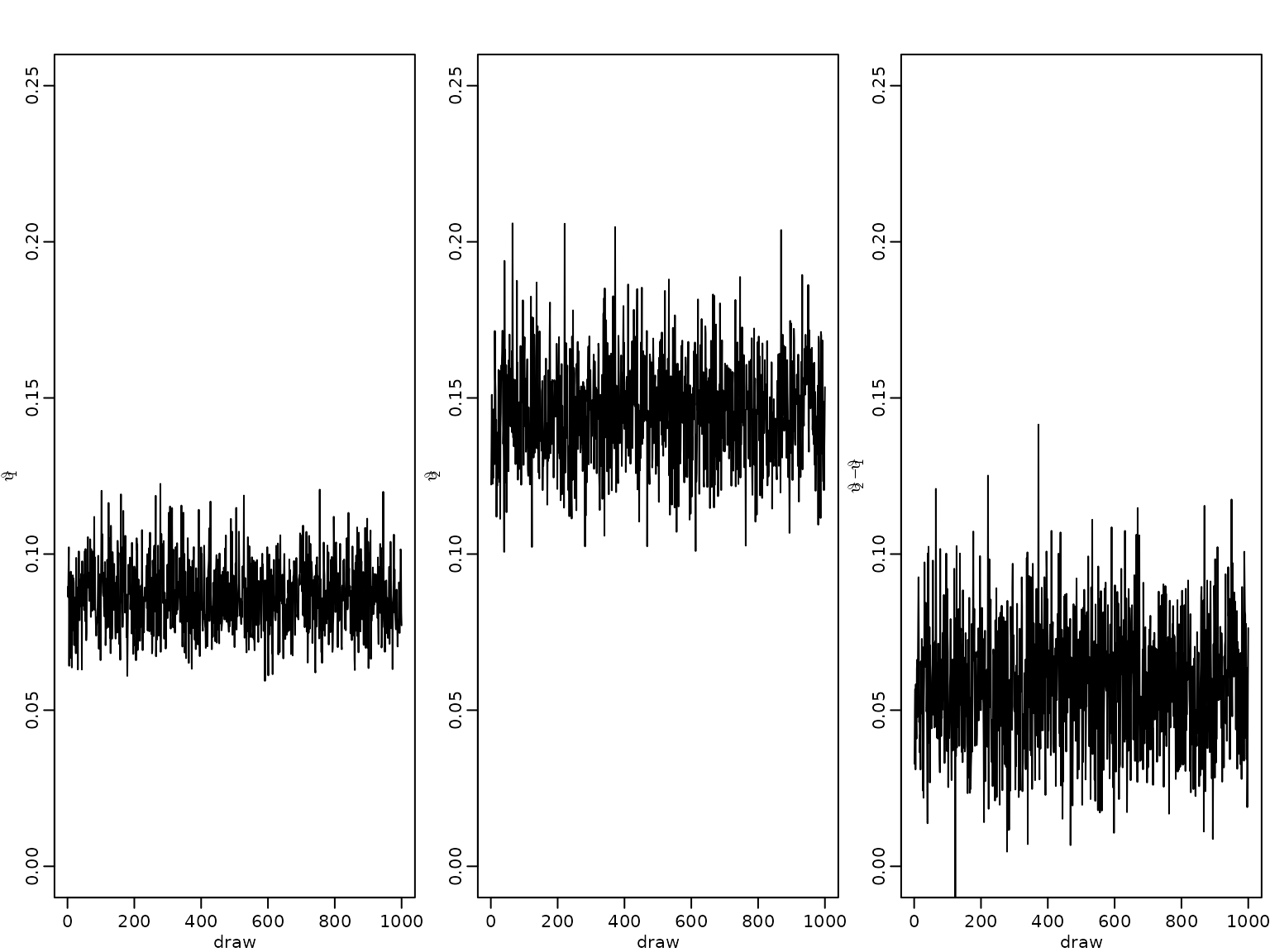

par(mfrow = c(1, 3))

labels <- c(bquote(vartheta[1]),

bquote(vartheta[2]),

bquote(vartheta[2] - vartheta[1]))

for (i in 1:3) {

plot(postdraws[1:1000, i], type = "l", ylim = c(0, 0.25),

xlab = "draw", ylab = labels[i])

}

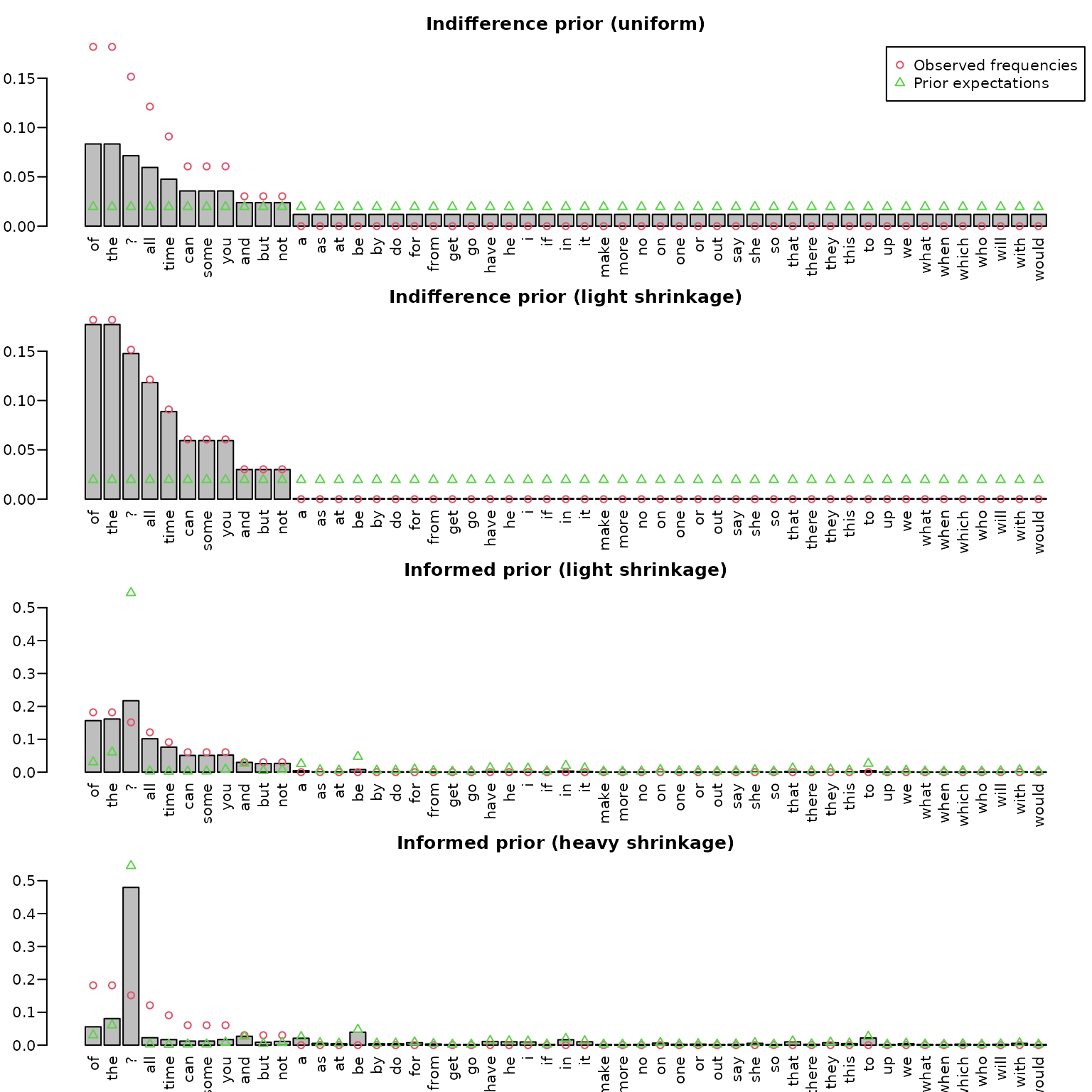

Example 3.5: Bag of words

Preparing the data

After reading in the quote, we do some simple manipulation such as converting to lower case, getting rid of newlines, and splitting the string into individual words. Finally, we remove potential empty words and display the resulting frequencies.

string <- "You can fool some of the people all of the time,

and all of the people some of the time,

but you can not fool all of the people all of the time."

tmp <- tolower(string) ## convert to lower case

tmp <- gsub("\n", " ", tmp) ## replace newlines with spaces

tmp <- unlist(strsplit(tmp, " |,|\\.")) ## split at spaces, commas, or stops

dat <- tmp[tmp != ""] ## remove empty words

tab <- table(dat)

knitr::kable(t(tab))| all | and | but | can | fool | not | of | people | some | the | time | you |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

To define our universe of possible words, we first look at the words dataset (shipped with this package). It contains 1000 most common English words, alongside their frequency of usage among a total of 100 million occurrences (cf. https://www.eapfoundation.com/vocab/general/bnccoca/).

data("words", package = "BayesianLearningCode")

head(words)

#> word frequency

#> 1 a 2525253

#> 2 able 47760

#> 3 about 192168

#> 4 above 25370

#> 5 absolute 9284

#> 6 accept 29026For illustration purposes, we only use the top 50 words and augment those with a question mark for all other words. This leaves us with 51 possible outcomes (our universe).

top50 <- tail(words[order(words$frequency),], 50)

universe <- c("?", sort(top50$word))

freq <- c(10^8 - sum(top50$frequency), top50$frequency[order(top50$word)])

universe

#> [1] "?" "a" "all" "and" "as" "at" "be" "but" "by"

#> [10] "can" "do" "for" "from" "get" "go" "have" "he" "i"

#> [19] "if" "in" "it" "make" "more" "no" "not" "of" "on"

#> [28] "one" "or" "out" "say" "she" "so" "some" "that" "the"

#> [37] "there" "they" "this" "time" "to" "up" "we" "what" "when"

#> [46] "which" "who" "will" "with" "would" "you"Now, we check if there are any words in our data set which are not included in our universe (here, only fool and people) and replace these with a question mark.

| ? | all | and | but | can | not | of | some | the | time | you |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

Computing the posterior under the uniform prior

Under a uniform prior (i.e., all 51 elements of our universe receive one pseudo-count), the posterior mean for each word occurrence probability is given by where stands for the number of data occurrences of the th word in the universe, and is the sum of all s. This can be very easily implemented by merging the universe and the data, and simply counting the resulting frequencies.

Computing the posterior under a less informative indifference prior

Note that the above strategy implicitly assumes that we have exactly 51 pseudo-observations. To render the prior less influential, we can rescale it to, e.g., 1 pseudo-observation. Then, the posterior expectation is To compute this expectation we simply add counts and the new pseudo-counts .

K <- length(universe)

N0 <- 1

gamma0 <- rep(N0 / K, length(universe))

post_lessinformative_unnormalized <- gamma0 + counts

post_lessinformative <-

post_lessinformative_unnormalized / sum(post_lessinformative_unnormalized)Alternatively, we could use a loop.

post_lessinformative_unnormalized2 <- rep(NA_real_, length(universe))

for (i in seq_along(universe)) {

Nk <- sum(dat == universe[i])

post_lessinformative_unnormalized2[i] <- gamma0[i] + Nk

}

post_lessinformative2 <-

post_lessinformative_unnormalized2 / sum(post_lessinformative_unnormalized2)The results must be numerically equivalent, and we can verify this easily.

Summing up what we have so far.

dirichlet_sd <- function(gamma) {

mean <- gamma / sum(gamma)

sd <- sqrt((mean * (1 - mean)) / (sum(gamma) + 1))

sd

}

resfull <- cbind(prior_mean = rep(1/K, K),

prior_sd_uniform = dirichlet_sd(rep(1, K)),

prior_sd_lessinformative = dirichlet_sd(rep(1/K, K)),

rel_freq = counts / sum(counts),

posterior_mean_uniform = post_uniform,

posterior_sd_uniform = dirichlet_sd(post_uniform),

posterior_mean_lessinformative = post_lessinformative,

posterior_sd_lessinformative = dirichlet_sd(post_lessinformative))

unseen <- counts == 0L

res <- rbind(resfull[!unseen,], UNSEEN = resfull[which(unseen)[1],])

knitr::kable(t(round(res, 4)))| ? | all | and | but | can | not | of | some | the | time | you | UNSEEN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| prior_mean | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 |

| prior_sd_uniform | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 |

| prior_sd_lessinformative | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 |

| rel_freq | 0.1515 | 0.1212 | 0.0303 | 0.0303 | 0.0606 | 0.0303 | 0.1818 | 0.0606 | 0.1818 | 0.0909 | 0.0606 | 0.0000 |

| posterior_mean_uniform | 0.0714 | 0.0595 | 0.0238 | 0.0238 | 0.0357 | 0.0238 | 0.0833 | 0.0357 | 0.0833 | 0.0476 | 0.0357 | 0.0119 |

| posterior_sd_uniform | 0.1821 | 0.1673 | 0.1078 | 0.1078 | 0.1312 | 0.1078 | 0.1954 | 0.1312 | 0.1954 | 0.1506 | 0.1312 | 0.0767 |

| posterior_mean_lessinformative | 0.1476 | 0.1182 | 0.0300 | 0.0300 | 0.0594 | 0.0300 | 0.1770 | 0.0594 | 0.1770 | 0.0888 | 0.0594 | 0.0006 |

| posterior_sd_lessinformative | 0.2508 | 0.2283 | 0.1206 | 0.1206 | 0.1671 | 0.1206 | 0.2699 | 0.1671 | 0.2699 | 0.2012 | 0.1671 | 0.0170 |

Computing the posterior under an informed prior

One might consider using yet another prior (which we label informed). For instance, we might want to fix the total number of pseudo-counts to, say, one fifth of the number of observations (this implies a data to prior ratio of 5 to 1). Each word in the universe is then weighted according to its frequency of appearance in the English language. Remember that the prior probability for a word outside of the top 50 English words is (the total number of words in the corpus) minus the sum of the top 50 counts. To compute the posterior, we can again add the actual counts and the new pseudo-counts.

N <- length(dat)

N0 <- N/5

gamma0 <- N0 * freq / 10^8

post_informed_unnormalized <- gamma0 + counts

post_informed <- post_informed_unnormalized / sum(post_informed_unnormalized)Alternatively, we might want to prefer heavier shrinkage with respect to the base rate (here, the overall word distribution in the English language). This can simply be accomplished by increasing the total number of pseudo-counts .

N0 <- 5*N

gamma0 <- N0 * freq / 10^8

post_informed_unnormalized2 <- counts + gamma0

post_informed2 <- post_informed_unnormalized2 / sum(post_informed_unnormalized2)Visualizing the results

To display the results, we use bar plots. We also add the prior probabilities of each word via green triangles and the observed relative frequencies via red circles. Sorting is done via frequency counts.

ord <- order(counts, decreasing = TRUE)

midpts <- barplot(post_uniform[ord], las = 2,

ylim = c(0, max(counts/N, post_uniform)))

points(midpts, counts[ord]/N, col = 2, pch = 1)

points(midpts, rep(1/51, length(midpts)), col = 3, pch = 2)

title("Indifference prior (uniform)")

legend("topright", c("Observed frequencies", "Prior expectations"),

col = 2:3, pch = 1:2)

midpts <- barplot(post_lessinformative[ord], las = 2,

ylim = c(0, max(counts/N, post_lessinformative)))

points(midpts, counts[ord]/N, col = 2, pch = 1)

points(midpts, rep(1/51, length(midpts)), col = 3, pch = 2)

title("Indifference prior (light shrinkage)")

midpts <- barplot(post_informed[ord], las = 2,

ylim = c(0, max(counts/N, post_informed, freq/10^8)))

points(midpts, counts[ord]/N, col = 2, pch = 1)

points(midpts, freq[ord] / 10^8, col = 3, pch = 2)

title("Informed prior (light shrinkage)")

midpts <- barplot(post_informed2[ord], las = 2,

ylim = c(0, max(counts/N, post_informed2, freq/10^8)))

points(midpts, counts[ord]/N, col = 2, pch = 1)

points(midpts, freq[ord] /10^8, col = 3, pch = 2)

title("Informed prior (heavy shrinkage)")

In the top panel (based on the uniform prior), we can nicely see the add-one smoothing effect, i.e., strong shrinkage towards the uniform prior, whereas the second panel shows almost no smoothing/shrinkage, and unseen words are estimated to be extremely unlikely. The two bottom panels show the posteriors under the informed priors, one with light and one with heavy shrinkage towards the prior.